Memory 2.0, A prelude.

Why are we still using ideas about memory from the 60’s to build programming tools?

As with the beginning of most fields of research, discovery is born from stumbles in the dark. Then beacons appear–theoretical stakes laid by early pioneers, a way for researchers to make sure-footed progress. But we were not meant to settle here.

Up to now, we have been building program tools based on conceptual models decades old, founded on psychology research that is even older. As one of the authors of a prominent conceptual model recently stated, “These models are being used long-past their shelf-life”.

For the programmer, almost no tool exceeds that of the brain and its ability for memory. Despite this simple observation, almost no programming tool is built based on our understanding of the brain and its ability for memory. Our conceptual models and theories still hold outdated views on the brain and memory.

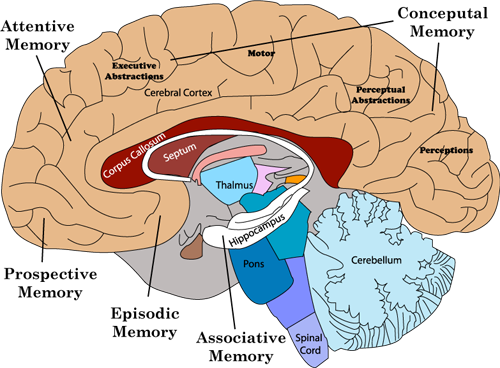

In my research, I building conceptual models for supporting programming tasks based on a theory that understanding the cognitive neuroscience of human memory is essential for understanding how to build tools that support programmers. In doing so, I abstract out some key concepts and principles about human memory from modern neuroscience literature, in a manner that (hopefully) allows researchers and toolsmiths to build better programming tools.

In no uncertain terms, programmers need our help. Despite human memory’s remarkable ability, memory stressors are chipping away at programmer’s productivity. Interruption devastates memory and continues to make tasks twice as long to perform, and have twice as many errors [Czerwinski 04]. In a study of such interruptions, Parnin and Rugaber [Parnin 10] analyzed interaction logs of 10,000 programming sessions from 86 programmers and found that in a typical day, developers rarely are able to program in long continuous sessions. Instead, a developer’s day is fragmented into many short sessions (15-30 minutes) interspersed with occasional longer ones (1-2 hours). Further, at the start of each of the longer sessions, a programmer often spends a significant amount of time (15-30 minutes) reconstructing working context before resuming coding.

Age is also becoming another relevant stressor on memory; as demyelination [Andrews-Hanna 07] begins just a few years completing a college degree, followed by the specter of ageism. As Stephenson put, Software development, like professional sports, has a way of making thirty-year-old men feel decrepit [Snow Crash]. Take a stroll down a google or EA office, teeming with thousands of 20-somethings, and handfuls of “ancient ones”.

In the next series of blog posts, I’ll talk about 5 types of human memory, and then some ideas for supporting them in our programming tools.

blog comments powered by Disqus