Memory 2.0: Attentive Memory

Continuing my series of posts on cognitive neuroscience of memory. In this post, I first give an overview of attentive memory, some examples of attentive memory failures, and then end with some thoughts on how we might want to support attentive memory in our design of interfaces and tools.

The frontal lobes is the most modern addition to the human brain, providing facilities for planning and reasoning about everyday tasks and social situations. Within the prefrontal cortex (PFC), lies amazing circuity for maintaining attention on important items during a task.

Attentive Memory

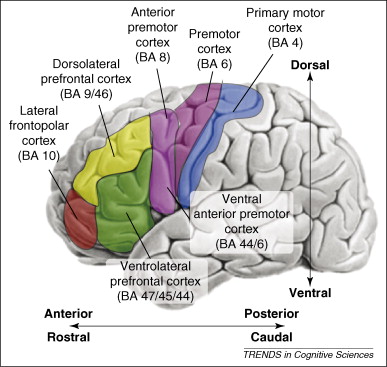

Attentive memory holds conscious memories that can be freely attended to. Within it, goals, plans, and task-relevant items can be sustained for substantial periods of time. Attentive memory is found in the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region situated in the anterior portion of the brain’s frontal lobe. One theory is that these regions provide the ability to maintain attention on modality-specific specific information such as visual targets in spatial locations or verbal information.

Attentive memory has two complementary operations with corresponding neural mechanisms: focusing and filtering.

Focusing

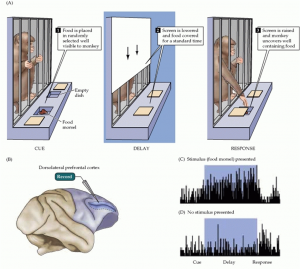

The ability to maintain focus on items has been well studied in the PFC of primates and humans. In early studies of monkey brains, when a food reward was shown to a monkey and then subsequently hidden for a delay period, persistent firing of neurons in the PFC was sustained during the delay period. Despite distracting stimuli, the monkey could recall the location of the food reward. However, monkeys with damage to the PFC could not maintain attention and performed poorly at recalling the location of the food [Fuster 71].

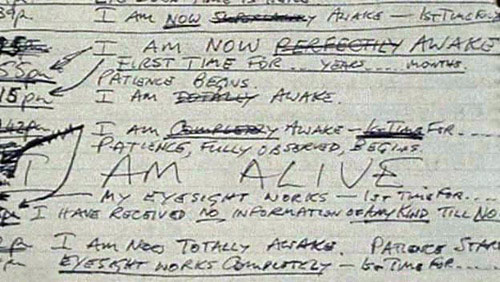

A human equivalent of these monkeys has been found in one patient, Clive Wearing. After a viral infection that destroyed much of his PFC and hippocampus, the patient could no longer attend to any memory longer than 30 seconds [Wearing 2006]. Definitely worth watching the documentaries: part 2a, part 2b,part 2c, part 2d; and more recently: “Man with the 30 second memory”.

Filtering

Humans can fluidly filter and switch among items in attentive memory using selective attention. Selective attention is the ability to conditionally attend to an item based on its attributes. For example, in a crowded room, attention can be switched from people with red shirts to people with hats. This ability derives from highly plastic neurons that can become tuned sensitize to certain attributes, such as color [Fuster 82]. Selective attention complements our ability to focus on multiple items by allowing distinct groups of items to be attended to. Thus, via selection attention, more items can be concurrently attended given that the items have distinct attributes [Park 2007].

Neural Mechanisms

More recent work has uncovered the underlying mechanisms of attentive memory. When examining the firing patterns of ensembles of neurons, rhythmic oscillations can be observed. These oscillations encode the attributes of an attended item. Siegel and colleagues [Siegel 2009] observed that when multiple items need to be attended to, distinct items were maintained in distinct phase orientations of the oscillating signal. Our limited ability to attend to multiple items are constrained by the speed and space it takes to encode waves within a limited frequency spectrum. An interesting benefit emerging from phase coding of items is the ``free’’ temporal order of those items. In the same experiment, when the order of items were misremembered, there was a correlation with inadequate phase separation of the encoded items: The signal still preserved enough information to represent the items, but not enough information was available to determine their order.

Why We Should Stop Using the Term “Working Memory”

Working memory is a conflated term based on outdated science.

The term working memory was first introduced in 1960 in Miller and colleagues’ influential book [Miller 60] on plans and reasoning as a system for temporary retention of plans and goals. The context of usage was for reasoning processes in cognitive models without strong considerations with concerns such as memory duration or task switching.

When Baddeley and Hitch first introduced their working memory model, they were concerned with the unitary view of short-term memory [Baddeley 2003]. What they wanted to emphasize was that short-term memory was not a passive store, but was interleaved with distinct modality-based processing of sensory input (separate verbal and visual processing). Further, they wanted to consider the low-level attentional processes needed to maintain those memories (over the time scale of seconds). What Baddeley describes can best be attributed to perceptual systems located in posterior regions of the brain. For example, patients with lesions to the left supermarginal gyrus (phonological loop) will have difficulty holding words in memory [Vallar 84]; whereas patients with a lesions in the right parieto-occiptial region have difficulty with spatial locations (for example, remembering a series of spots pointed to by another person).

Unfortunately, researchers across multiple disciplines have conflated the different usages of these terms to mean the same thing – that a perceptual store is the same as an ``temporarily indefinite’’ pool of memory. That is, when referring to something such as the working memory of a programmer, a researcher is most likely meaning it in the sense of Miller and not Baddeley. Baddeley’s working memory theory cannot account for how people perform complex tasks or recover from interruptions. Theories such as long-term working memory attempt to reconcile this difference, but offer no neuroscience basis for the theory [Ericsson 95]; leaving some researchers to suggest the standard model of working memory has outlived its usefulness [Postle 2006].

Finally, recent evidence confirms that activity in neurons in the PFC are related to attended items and not remembered ones [Lebedev 2004].

Programmers and Attentive Memory

What are attentive memory failures that workers like programmers face?

Some programming tasks require developers to make many changes across a codebase. For example, if a developer needs to refactor code in order to move a component from one location to another or to update the code to use a new version of an API, then that developer needs to systematically and carefully edit all those locations affected by the desired change. Unfortunately, even a simple change can lead to many complications, requiring the developer to track the status of many locations in the code. Even worse, after an interruption to such as task, the tracked statuses in attentive memory quickly evaporate and the numerous visited and edited locations confound retrieval.

Supporting Attentive Memory

Given the volatile and limited nature of attentive memory, how can we better support it in our tools and interfaces? In general, a tool should provide a mechanism for a persisted and stateful focus, on a numerous items, with various modalities.

In programming environments, code tabs are a central but limited interface element for supporting attentive memory [Ko 2006]. Bookmarks are another supportive but rarely used device. Arguably, Mylyn offers a good start. It is a programming tool that offers attentive memory support, by providing an ability to focus and filter programming files based on those that were visited or edited during a task. However, there are still several short-comings. For example, the focus mechanism is binary (degree-of-interest aside), and does not include stateful properties such as status of an unresolved issue or whether an item is edited or visited (which I might want to know if I’m in the middle of making a change to hundreds of locations).

In desktop environments, the Task Bar in Windows or the Dock in Mac OS offer attentive memory support for applications and documents. Browsers also use tabs. None of these are super. Research has looked at how to improve these, such as approaches offering spatial modality: Scalable Fabric, more structure: GroupBar, and temporal and visual modalities: WindowScape, RelAltTab.

Most of these designs were devised before we had a deeper understanding of the brain. How can we rethink some of our design decisions with a better understanding of the brain and its support for memory? Our understanding of attentive memory is still growing, but one thing we can start asking ourselves is: What are the attentive memory failures that a user may face, and what are the interface elements that I can provide to support them.

blog comments powered by Disqus