Java Generics Adoption: How New Features are Introduced, Championed, or Ignored

Following a successful collaboration with Emerson Murphy-Hill on “How We Refactor, and How We Know It”, we decided on doing another empirical study, this time on Java generics. Turns out Christian Bird had similar interests, so we banded together for a new paper recently accepted for MSR’11.

Adding features to a programming language is a difficult prospect. Politics, committees, compatibility, and egos don’t make it any easier. And once a feature has finally made it and shipped, there is a whole other question of how does it plays out? Did designers get it right, does adoption occur? Does the promises of the new feature actually solve the software developer’s pain? How do developers decide to use a new feature, do they plan to migrate old code, coordinate coding standards?

To look at these questions, we looked at how Java generics were adopted in open source projects, which was officially released in 2004. There has been a long history of infighting and arguments for adding generics from the very start. For example, generics were strongly argued for in Guy Steele’s 1998 OOPSLA Keynote, “How to Grow a Language”.

In the process, we analyzed a half billion lines of Java code across the entire lifetime of 20 Java projects to see how the projects grew to use generics or not. We looked at these basic questions (see paper for those in gray, results are shown below for those in black):

-

What percentage of projects and developers used generics?

-

What was the breakdown of feature use?

-

What was the impact on casts after generic adoption?

-

What was the impact on code duplication on container classes?

-

Was there an effort to migrate old code to use generics?

-

Was the adoption of generics concerted (did every start using it at the same time)?

-

Did support of generics in the IDE have an impact on adoption?

We found over half of the projects and developers we studied did not use generics; those that did restricted their use to type-safe containers. Few created generic classes, and even fewer created generic methods.

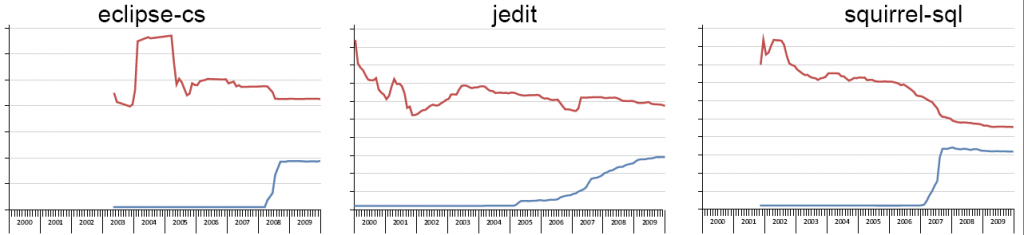

We found generics were not correlated with a reduction in casts for most projects, despite claims this should happen. Number of casts normalized by project size (red) versus generic usage (blue) over time:

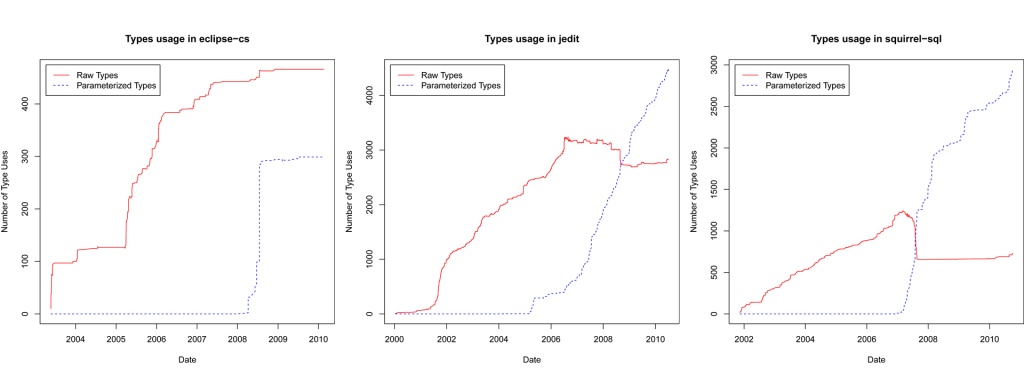

We found that most projects did not convert a large percentage of “raw” types (List) to generic types (List

Finally, we found that the decision to use generics was mixed among developers in the same project. Some developers stubbornly used “raw” types despite adoption by others in the same project, whereas, in many projects that did use generics, there was a single developer who “championed” the use of generics, by using generics much earlier and in larger amounts than other developers.

Even when the battle for releasing a new feature has been won, the war may continue on in much larger fronts within the trenches of software development. Developers still have to struggle with migration efforts and settle the same heated debates the designers originally had. Collecting empirical evidence early, providing migration tools and support, and building community support through social media should be standard practices for researchers and designers releasing features to the wild.

To see more detail on this and other questions, see a draft version of the paper.

blog comments powered by Disqus